How Much Does A Patent Cost?

Updated 23 July 2023

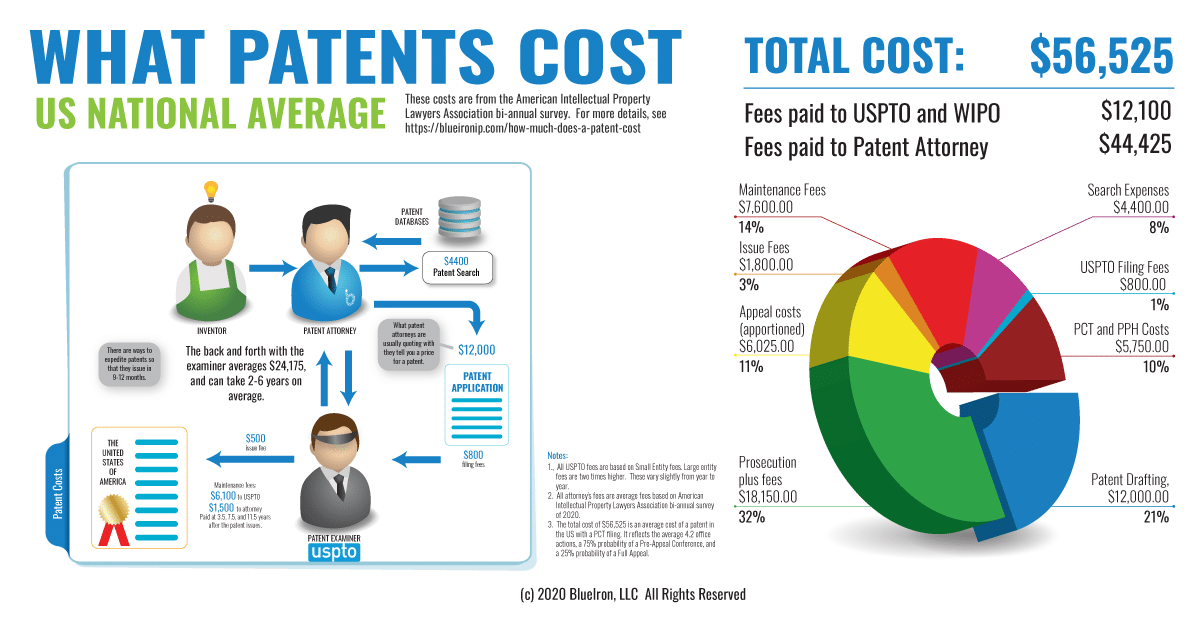

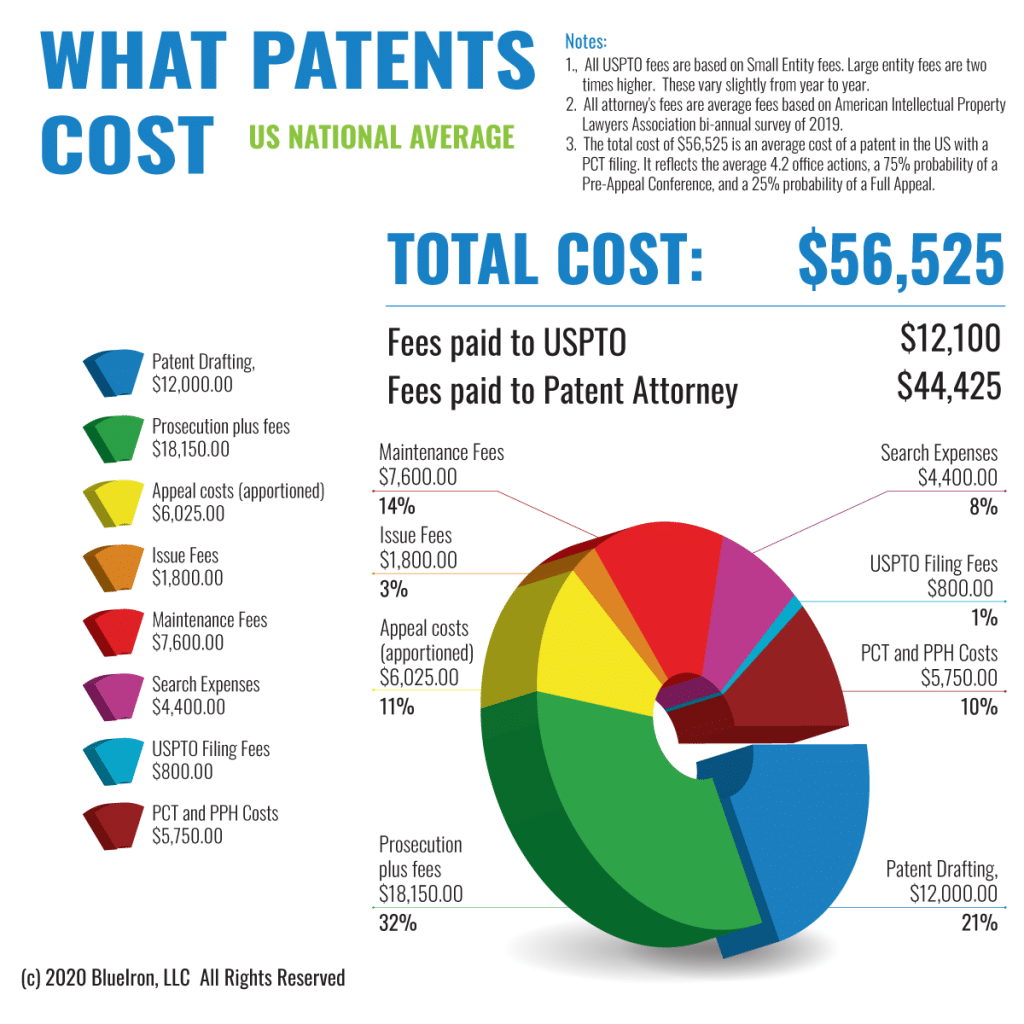

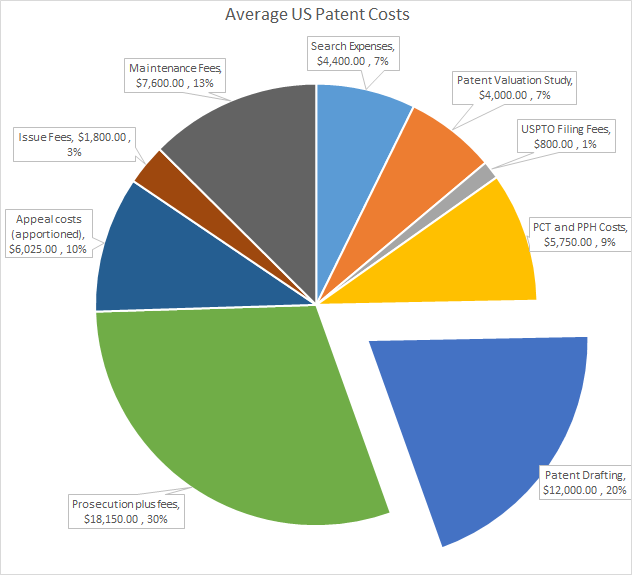

The average cost of a utility patent in the US is over $50,000. This is just the cost to file a utility patent application and the patent examination process. It does not cover the cost of enforcing your patent, which can be in the millions.

All patent owners should have patent insurance. Insurance allows you to enforce your patent, as well as survive an inbound lawsuit from another patent owner. If your intellectual property is valuable, it should be insured. If it isn’t valuable enough to be insured, why do you have it?

The figures below come from the latest AIPLA bi-annual survey. Please note that this will vary widely – especially because the amount of back and forth with the patent examiner can be one or two Office actions – or it can be brutally long, going on for 10+ years.

| Stage: | USPTO Fees | Average Patent Attorney Fees |

| Pre-filing professional patent search | – | $1,500-4,000 |

| Drafting and filing – biotechnology/chemistry | $660 | $11,400 |

| Drafting and filing – electrical/computer | $660 | $10,923 |

| Drafting and filing – mechanical | $660 | $9,500 |

| Amendment/Argument after rejection | $0-660 | $2,300-4,000 |

| Examiner interview | $1000-2000 | |

| Misc fees (assignments, information disclosure statements, declarations, power of attorney, etc.) | $1500 | |

| Issue fee payment | $480 | $1500 |

There will be, on average, 4.2 office actions/rejections per utility patent. Some utility patents will issue right away, and some will take a lot of back-and-forth with the examiner. One dirty little secret about patent law is that patent attorneys make more money on the back-and-forth, but they never tell you that up front.

In this post, we look at a lot of things regarding patent costs:

- What are the basic patent costs?

- What are the costs to just file a patent?

- Is micro entity worth it?

- Is a provisional patent application cheaper? (NO!)

- What can I do to expedite my patent?

- What are the costs for software patents?

- What can affect patent costs?

- What does it cost to patent worldwide?

- My attorney says they can do it for much less…

- Should I pay my attorney by the hour or fixed fee?

- Is it better to have Big Law do my patent?

- Is there any difference between patent agent and patent attorney?

- What are the detailed costs for a patent?

- Financing the cost of a patent.

Basic Utility Patent Costs

How much does a patent cost[1]? The US average *just to file a utility patent* is about $12k, but the total cost of a patent is closer to $50k.

Have you been quoted much less? There are plenty of patent lawyers who quote much less than $12,000 to draft a utility patent application. But beware. One of the standard practices is to quote a much lower fee to draft the patent application, but they make it all up with the back-and-forth with the Patent Office.

“My attorney quoted much less than $12,000”

Some attorneys will quote as little as $2000 to $6000 to write a patent application. But don’t be fooled. The dirty little secret is that the worse the initial patent application is, the more money the patent attorney can make by all the “patent prosecution,” (which is the arguing between the attorney and the patent examiner).

A typical US patent costs around $50,000, according to data from the American Intellectual Property Legal Association bi-annual survey. This is the average cost across the US for a patent on a “high technology” invention, and your mileage may vary. This price is highly variable – sometimes it will be less, and sometimes much, much more. For a financing solution that makes the fees predictable and uniform, see BlueIronIP.

The patent costs are broken into drafting or writing the application (“preparation”) and prosecution. Preparation includes everything to get you to “patent pending” status, then prosecution is everything from filing to issue. Preparation is understanding the invention, drafting the claims and the specification, getting the illustrations done, and the odds and ends that need to be done to file the patent application with the US Patent and Trademark Office. Remember that every word in a patent application hurts you, and this is why you need a competent patent attorney to write your application.

The prosecution portion is going back and forth with the Patent Office. The examiner issues an Office action rejecting the claims, and the attorney/agent responds. This back-and-forth can be frustrating at times, but is a necessary part of making sure your patent is strong. The industry average is 4.2 Office actions per case. Just because your patent was rejected initially, that is not a bad thing.

What are the costs to just file a patent application?

Filing a patent application will cost you about $8000 to $15000 for the attorney, and $830 (approximately) for the USPTO filing fees, assuming a “small entity.” (I recommend NEVER filing as a “micro entity,” as there are some loopholes that are not worth the tiny cost savings.)

Some attorneys will charge significantly less, sometimes $4000-6000 to write a patent application. Is this a good bargain? Do you shop around for the lowest cost surgeon when you have a critical operation?

Do I want to file as a “micro entity”?

I do not like the “micro entity” option that the USPTO offers. It has some problems that are not worth the risk. In the end, shaving a few pennies puts your patent at risk of being invalidated by a simple error.

The key to micro entity is that you must notify the Patent Office when you no longer qualify. Most people qualify for micro entity because they have low income AND have filed only a patent or two. At some point, you will have more patent applications in process or your income might exceed the threshold. If you forget to change the entity status – and it is very easy to forget – you may save a couple hundred dollars on a filing fee but can be accused of committing fraud on the USPTO. This will invalidate the entire patent.

Is it worth the risk to invalidate a patent (which is supposed to be worth millions) just for a few hundred dollars? No.

Note that some entities, like universities, have “micro entity” status that never changes. For them, they should always take advantage of the program.

Is a provisional patent application cheaper than a non-provisional patent application?

No! Provisionals are always *more* expensive, plus there are huge risks with provisional patent applications. Some attorneys will charge as little as $2000 to “write” a provisional patent application, but then charge you much, much more to write a non-provisional application a year later. The filing fees for a provisional patent application are less than a non-provisional, but you will still have to pay the non-provisional filing fees a year later. Your net expense will always be higher if you file a provisional.

Provisional patent applications are always – without exception – the wrong thing to do for a startup company. In almost every scenario, it is better for a startup or early stage company to get patents fast, rather than slow. It makes them better investments, allows them to license their technology, helps them raise money, and makes them eligible for patent-collateralized loans.

It is common practice for a patent lawyer to sell an inventor a “cheap” patent application. Even the USPTO actively promotes a provisional application as something that a startup or independent inventor should do.

The real reason why a provisional patent application exists is that there was a loophole for foreign companies who file in the US to get an extra year of patent life. By creating the provisional patent application, US companies were given the same opportunity to *delay* getting a patent.

In practice, provisional patent applications are a way for Big Companies to extend the life of their patents. By filing a provisional application then waiting a year to file a non-provisional, the US created a way to extend the 20 year life of a patent to year 21.

Who cares about having a patent that goes from year 20 to 21? Big Pharma companies. They make all their money at the end of the patent life.

Do startups care about patent life in year 20? NO! Startups are worried about getting value as soon as they can.

What can I do to expedite my patent?

There are a number of programs that the USPTO has for expediting patents. In most cases, you can get a patent within a year.

Without question, Track One is a flawed mechanism for expediting a patent. It should *never* be used unless the client understands the huge downsides.

The best program for expediting a patent – and one that is cheaper than Track One[2] – is the Patent Prosecution Highway. With PPH, you file a PCT (or other international application with expedited examination) and, once you have a favorable reading from the examiner, you get ‘special’ status in the USPTO.

The ‘special’ status means the examiner must reply in 10 days – even if the examiner is on vacation (unless the vacation is 4 weeks or more).

How much does a software patent cost?

Many attorneys charge $15,000 or more for patent applications for software, but the truth is that they are actually easier than so-called “simple” mechanical inventions. Software patents get the high price tag because that is what the market will bear, not because they are any harder than other technologies.

Patent applications come in two parts: preparation and prosecution. The preparation part (just writing the patent application) is what you are usually quoted, which might be $15,000. The prosecution part is the back and forth with the examiner. This is where the patent lawyer makes most of their money. It can cost another $30,000 or more during this phase.

Software patents have received lots of attention over the years. But “software” always has been – and always will be – patentable, even though there are plenty of issues with software patents. There are roadblocks that need to be navigated, but it really is not a big issue when you have competent counsel.

Writing a software patent is not difficult, but if your patent attorney is not familiar with the patentable subject matter issues around 35 USC 101[3], the prosecution costs of your patent can be astronomical. This part of the patent application process is the real cost of a software utility patent.

What can affect a patent’s cost?

The single biggest factor in reducing a patent’s cost is:

- Doing a good search and refining the invention based on the prior art.

- Designing the patent – intentionally – to avoid the prior art.

Many people skip the patent search, or do only a cursory search.

By the way, it is never a good idea to have your patent attorney do a patent search, purely because of the conflict of interest. Patent attorneys will never tell you that they should not write your patent – they would lose money if you don’t. Any time the patent lawyer does a search for you, they can “put their finger on the scale” when giving you the results.

It is a best practice to find someone who has no financial incentive to do your patent search. Personally, I use Techson IP’s Limestone reports.

It is true that the only search that matters is the one that the examiner does. But if you do not know the prior art before filing, you are shooting in the dark. There is always a good chance that someone has already thought of your idea.

What does it cost to patent an idea worldwide?

The basic process for “world-wide” patent coverage is to file a Patent Cooperation Treaty (“PCT”) application, then enter each and every country a couple years later. This is very expensive, and it is not uncommon to spend $500K or more to get patent coverage in a large number of countries.

In general, the US is one of the best bargains for the cost of patent, since a single patent that may cost $60,000 covers a population of 300M+. For covering the same population in Europe, the cost may be ten times as much.

The biggest cost in international filing, aside from the one-time translation costs to each language, is the annual annuities. These fees can easily exceed $1000 per year per COUNTRY. With 190 countries as part of the PCT, the lifetime cost of a “world-wide” patent can reach into the tens of millions.

My attorney says they can do a patent for much less.

Have you been quoted much less? There are plenty of patent lawyers who quote much, much less than $12,000 to draft a patent application. But beware. One of the standard practices is to quote a much lower fee to draft the patent application, but make it all up with the back-and-forth with the examiner.

Some attorneys will quote as little as $2000 to $6000 to write a patent application. But don’t be fooled. The dirty little secret is that the worse the initial patent application is, the more money the attorney can make by all the “patent prosecution,” which is the arguing between the attorney and the examiner.

What is your patent worth? If your patent protects a multi-million dollar investment in your intellectual property, isn’t it worth spending the time and money to do it right?

Sometimes you get what you pay for. Your intellectual property is not where you want to skimp.

Should I pay my attorney by the hour or fixed fee?

There are two schools of thought about legal work: billing by the hour or a fixed fee per project. Neither one is perfect, but the advantage goes to fixed fee billing – at least for patent work.

The simple fact is that billing by the hour encourages an attorney to work very slowly, while billing by the project encourages them to work very fast. A worker paid by the hour can “pad the bill” to inflate an invoice, and it is impossible to tell that it happens. A worker paid by the project can cut corners to get something out the door quickly.

Which is best?

I began my career in patent law as an inventor. I went to a patent lawyer that I knew, and he billed by the hour. Every conversation was slow, methodical, and he went over everything multiple times, mostly to fill the air time and run up the meter.

The other part of the equation was that he would never give business advice.

When I went out on my own, I began billing by the project. I felt that I could do a good job for my clients and not need to cut corners because I was charging a fair price. I tend to write very quickly and without a lot of errors, so I would consistently under-bill projects when I worked in a bill-by-the-hour law firm.

My personal preference is the fixed fee, both as a client and as a service provider. The bills are known and do not have surprises in them, and since I happen to be efficient, I can focus on quality without feeling like I am losing money on a project.

Is it better to have Big Law Firms write my patent application or smaller firms?

Read more about Big Law and patents here.

Many inventors and entrepreneurs like to tout their relationship with a Big Law Firm. It is too bad they do not know how the sausage gets made. However, small firms are not without their problems, too.

Big Law is all about churning work through the machine. In general, partners bring in the work, then feed it to the associates. The partner is the client-facing person and gets paid a percentage of the billings, but the real work is done in the windowless back room.

Big Law makes most of their money with Big Clients. The Big Clients often are smart enough to tell the partner that they want to vet every attorney who touches their work. When I did a lot of patent work for Microsoft, they wanted to run every attorney through a qualification process, and if they found out someone who was not qualified by them was working on their matters, the entire law firm was fired.

So, how does a first year associate get any work to do? It is from the small clients – especially when the small clients want to “save money.” If you think your work is being done by the big partner in the Big Law Firm, you are mistaken. The partner may “review” the work, but it is essentially the chum that they use to train their associates who are too unqualified to work for the firm’s real clients.

I am being somewhat facetious here, but you get the point: it is a factory at Big Law and your work is probably not getting the love it deserves.

What about small firms? Some are fantastic, where you talk to the actual person who is doing your work, and they are small, nimble, and have great customer service. In many cases, the attorneys have exceptional experience and can be a big value.

On the other hand, you might run across a small firm with virtually no real-world experience.

How to find a good attorney? Use the process in this blog post entitled “How to Find a Good Attorney.”

Why are legal fees so high?

Law firms have a structure that is inherently costly. In a typical law firm, 1/3 of your fees go to administration, 1/3 of your fees go to the partner managing your case, and 1/3 of your fees to go the associate who does the work. While this is true of the large law firms, smaller typically charge less mostly because they don’t have to support this enormous overhead.

Many startup companies see the allure in using big name law firms. Many startup companies do not realize that Big Law is often using a startup’s work to train their first year associates. Not only do you get the Big Law prices, you also get first-year associate work product.

Smaller law firms might be a good fit.

You need to find a good fit between your company and your law firm. You want your lawyer to answer the phone when you call and give you the attention you deserve. Many times, you will get the best service at law firms that resemble your company.

Giant corporations use giant law firms for many reasons, but the biggest reason is that larger clients have issues that take lots of manpower and can have huge financial implications to the clients.

Smaller corporations use smaller law firms because these clients get the attention they deserve. The client is a meaningful and important part of the firm’s revenue, so the lawyers are responsive and attentive.

Is there any difference between a Patent Agent and Patent Attorney?

The difference between a patent agent and a patent attorney is merely that the patent attorney went to law school.

Both the patent agent and the patent lawyer have to have engineering or science degrees, and both have to pass the same Patent Bar Exam. Both of them have the same rights, privileges, and responsibilities before the USPTO.

I began as a patent agent, then went to law school and became a patent lawyer. My joke was that I spent three years in law school and wound up doing the same work for the same clients for the same amount of money.

Functionally, there is no difference (although the patent lawyer can get you out of your speeding ticket, too.) Patent agents can be every bit as good as patent lawyers – and every bit as bad sometimes.

Practically, patent agents are treated as second class citizens, but mostly by the attorneys. The American Bar Association – who has a monopoly on how our legal system works – has put local laws in place that prohibit non-attorneys from being partners with attorneys. So, a “law firm” run by an attorney cannot be co-owned by a patent agent.

This is purely an artificial constraint that forces people to go to law school (accredited by the ABA) then join the local bar (and pay their dues to the ABA).

Detailed cost breakdown for patents:

The average US utility patent cost between $30,000 and $60,000. The data below are derived from the American Intellectual Property Lawyers Association Bi-Annual Economic Survey, available here.

The patent process involves two major phases. Patent “preparation” is when the utility patent is originally drafted and filed with the patent office, and patent “prosecution” is the back and forth that happens with the examiner. Typically, the patent preparation phase is what an attorney will quote a client, but it is often only 25% or so of the total.

Here is a breakdown of the average patent cost from the report:

Preparing and filing a typical utility patent (relatively complex): $12,000

Office action responses: $4000

Novelty search: $4000

Other things we need to consider:

USPTO filing fees: $800-1600 (depends on small/large entity status)

PCT filing fees: $2500-3500 (depends on page count for application)

An average utility patent takes 4.2 office actions to get allowed. Yes, some patents are allowed sooner, but many are allowed after 6-10 office actions. Also, remember that for every 2 office actions, a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) fee of $800/$1600 is incurred.

A pre-appeal conference is often useful in moving cases towards allowance, and this is approximately the cost of an office action response. This occurs in about one out of every two cases, but sometimes two or more times per case. My experience is that I use it almost one time per case on average. This adds a $800 appeal fee as well.

There is a possibility of a full appeal, which costs $10,500, but this only occurs in about 12% of the cases based on my personal experience of about 1000 cases.

The office actions is where a significant amount of expense is incurred.

Total costs:

Filing (including a search and USPTO/PCT fees): $22,250

Prosecution:

4.2 office actions plus RCE fees: $17,550

Pre-appeal conference: $4,000 (75% likelihood)

Full appeal: $10,500 (25% likelihood)

Total prosecution costs: $24,175

Issue fees: $1800 (includes both attorney fees and USPTO fees)

Maintenance fees: $7600 (small entity prices)

Total: $60,525 (average patent cost) plus or minus.

Financing the Costs of a Utility Patent

BlueIron is an alternative funding source for startup companies. We provide $50-100K investments for developing patent portfolios for startups. What is the catch? We only invest when we believe the patents are going to be in that sliver of super-valuable utility patents.

Our due diligence focuses on the potential value of a company’s patents, but also on whether the company will be able to turn those ideas into actual value. If you pass our due diligence, you know those patents are going to be very high value.

Schedule a call to get your patents analyzed.

References

- Patent Costs in Investing in Patents, Appendix B (Book) ↩

- Getting Patents Fast in Investing in Patents, Ch. 4 (Book) ↩

- 35 U.S.C. 101 – Patent eligibility ↩