How Patent Licensing Works

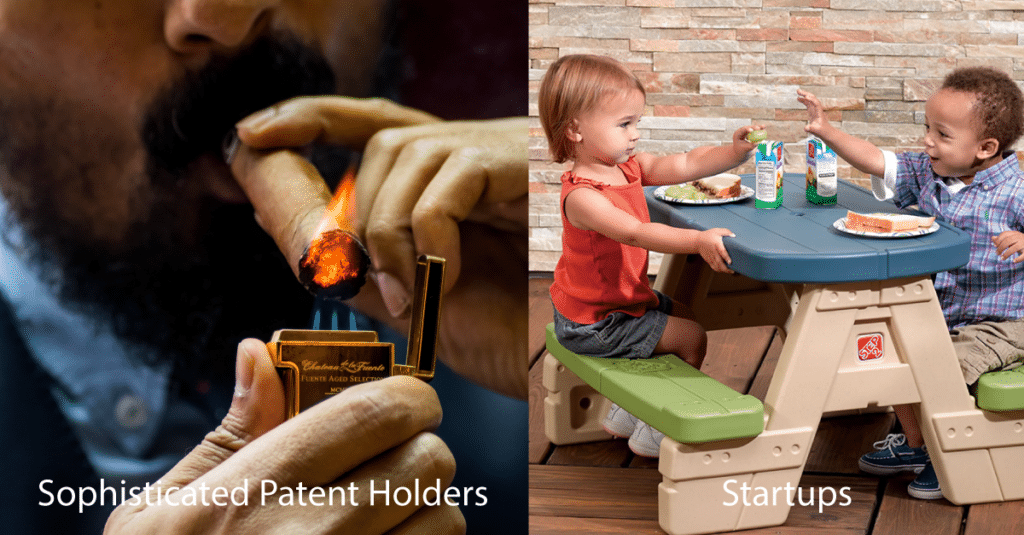

On a small scale, a patent owner might worry about creating patents that can be asserted against competitors. The plan is to stop a competitor from copying. These thoughts are often where a startup stops the analysis.

This concept is the essence of a good patent. But what happens when you get the patent? How does it actually get put to use?

The “grownups” use licenses.

Big companies use their patent rights in a completely different way than startups. There were 3,300,000 enforceable patents in the US in 2020, but only a paltry 4000 patent lawsuits.

Yet, large entity patent owners (those with more than 500 employees) file a lion’s share of all patents. Why would a company spend $50,000 each on hundreds of patents a year?

The biggest use of patents is not going to court to litigate against an infringer. It is patent licensing.

Usually, it is some form of cross licensing.

Cross licensing comes in several different flavors: the “silent cross-license,” an explicit cross-license, and patent pools.

Silent cross-license

A “silent cross-license” is a patent license where two intellectual property owners each have patents that the other infringes. But neither one wants to begin Mutual Assured Destruction with a giant lawsuit. One of the biggest “silent cross-licenses” is between Google and Microsoft. Each company has tens of thousands of patents, but neither company wants to start a war to end all wars.

Rest assured, both competitors know each other’s patent portfolios and their products. But neither company wants to assert a patent against the other for one product, only to find out that they infringe 10 patents that the other side owns.

Silent cross-licenses happen when two fierce rivals are not willing to talk with each other, but mostly they occur because the patent owners want to avoid anti-trust issues.

An anti-trust problem can happen when two companies appear to be colluding.

Let’s say we have two major players who dominate the market. Any licensing agreement to cross-license their IP would be seen as colluding, triggering an anti-trust issue. The anti-trust issue is that a much smaller third competitor would not have access to the IP of the big, dominant players.

A good patent strategy for a silent cross-license is to write a lot of patents. The more ammunition you have, the better.

Explicit cross-license

An explicit cross-license is a form of patent licensing where two patent owners with complementary patents agree to terms. They may agree to a no-cost cross patent license, where money never changes hands. This form of patent licensing agreement is never an exclusive license. It is always a nonexclusive license.

In most cases, one of the companies brings a bigger stack of patents to the table than the other. The company who has the smaller stack of patents winds up paying a license fee. The company with the larger stack of patents gets paid.

The patent strategy for any explicit cross-license is to write a lot of patents. At first glance, the sheer number of patents is important, at least for the initial posturing.

A cross license agreement may be limited or unlimited. In an unlimited cross license, all of the patents for one company are licensed to the other.

Most cross licenses are limited to certain products or technologies. A multi-national conglomerate may do a cross-license between one of their business units with a small, single-product company. The multi-national company may license only a portion of their enormous portfolio that the smaller company needs. The smaller company may license its entire portfolio.

Joint venture agreements and patent licenses

Patent licensing is a big part of joint venture agreements. In a joint venture, there is a shared business arrangement where both companies take part in building a specific technology or business. As part of the joint venture, both companies contribute their IP.

Usually, there is a strategic element of the joint venture, where the patent owners are agreeing to develop additional intellectual property, or they are doing a joint marketing/sales venture.

These license agreements need to specify who owns any intellectual property that is developed from the joint venture. Sometimes, both companies share in the intellectual property. In other cases, one company might be the patent holder, while the joint venture agreement may give a license to the other party.

Patent pools

Patent pools are the Holy Grail of patent licensing. A patent pool is an organized body that collects patents from several licensors or patent owners. The pool then licenses these patents to others, known as the licensees.

Patent pools originated in the 1890’s when three different sewing machine manufacturers each had patents that blocked the others. Because of these blocking patents, all of the sewing machine manufacturers were dead in the water.

The idea of a patent pool was to gather the patents together, cross-license them to each other, but also to other companies in the industry. A license agreement under a patent pool is typically under Fair Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (“FRAND”) basis. This type of patent licensing allows anyone to have access.

Today, patent pools are done for specific industry standards, such as MPEG, JPEG, WiFi, various compression algorithms, and a host of others. Patent pools are also gathered together for general technologies, such as Electric Vehicle Charging.

Patent pools are one of the most sophisticated ways to grant licenses. The pool managers identify a group of patents, which may be owned by several companies. In exchange, a licensee gets the freedom to make or sell products using those patents.

Sometimes, a patent pool is formed around an industry standard. Here, each patent owner that contributes to the standard’s technology gets rewarded by receiving royalties.

Exclusive vs Non-Exclusive Patent Licenses

Exclusive licenses

An exclusive license is a patent license agreement where one licensee gets all rights to a patented invention. The licensee is exclusively granted the rights to make, import, or sell the patented invention.

An exclusive patent license agreement is valuable because only one person – the licensee – has the right to make the patented invention. This gives the licensee a competitive advantage because nobody else can make the same product. However, the license agreement must specify who has the obligation or option to enforce the patent.

Exclusive licensing can give the right to enforce the patent against an infringer. In this situation, the licensee can sue an infringer and collect royalties. When a license agreement gives the licensee the right to sue, the royalty rates are typically lower than if the owner enforces the patent. This is because the licensee must put up the money for a patent lawsuit.

Sometimes, a patent owner has the right – and responsibility – to go after infringers. The owner must pay for all litigation. Sophisticated patent owners in this situation will typically have patent enforcement insurance to cover the risk of enforcing under this type of exclusive licensing.

Non-exclusive patent licenses

Non exclusive licensing is a way to license a patent many people may take a license to intellectual property rights. Nobody has the exclusive rights to the patented invention, so each licensee can make, import, or sell the product.

Cross-licenses and patent pools are examples of non exclusive licenses.

Under non exclusive patent license agreements, the patent owner has the right to enforce the patents against infringers. The owner will enforce their patents to have the infringer cease and desist from practicing the invention, or the owner may try to get them to license a patent.

No company likes to pay to license someone else’s intellectual property rights.

The only real reason why someone would take a patent license is the threat of a lawsuit.

However, if the infringer has a valuable patent portfolio of their own, they can often turn patent licensing agreements into cross licensing agreements. In other words, they trade their intellectual property with a patent owner.

This is the single biggest use of intellectual property in industry today: patents as trading cards. In fact, most large corporations have huge patent portfolios not for outbound licensing. They use it for trading with competitors using cross licensing agreements, joint ventures, and occasionally, patent pools.

Patent trolls and patent licensing

The world of patent licensing has existed for nearly a century. It began with the sewing machine patents in the late 1800’s. Another patent pool was set up between the Wright Brothers and Curtiss Aircraft in the early 1900’s. Patent pools have been a staple of major shifts in technology, including radios, television, and countless examples in computer technology.

In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, patent licensing had a sea change when “non-practicing entities” or “patent trolls” began acquiring patents from defunct dot-com-era companies and asserting the patents. The term “patent troll” was coined as a pejorative public relations term to demonize the practice.

Essentially, big firms were used to cross-licensing their technology when they got sued.

However, when they were sued for patent infringement[1] by non-practicing entities, they could not cross-license. They could only pay. And the big companies hated this.

Like anything in business, once someone was successful with a strategy, many people followed. Countless inventors would sell their invention to a patent assertion entity, who would strongarm infringers to license the patent.

Several law firms and businesses were very successful at getting patent licensing agreements with major corporations. They made millions, if not billions, of dollars with this strategy.

Industry response to patent trolls

Industry took a dim view of patent trolls and has successfully tarred “non-practicing entities” for nearly two decades.

There have been two major efforts to combat this perceived problem: undermining the patent laws and efficient infringement.

Undermining patent laws

Big Tech has fought relentlessly to undermine the patent laws over the last two decades.

The biggest change was in eBay vs MercExchange in 2016, which decimated the patent holder’s ability to stop the infringement immediately.

It used to be that a patent owner would go to court, assert that Big Company was infringing their patent, and the court would shut down the Big Company immediately. A Big Company with a billion-dollar a year product would pay whatever they needed to settle the lawsuit. It used to be that a simple cease and desist letter was successful at eliminating 95% of all patent lawsuits. Sadly, this is no longer the case.

An injunction was an enormously powerful weapon that gave a United States Patent a huge amount of respect.

Because of the threat of injunction, companies would routinely perform clearance searches or freedom to operate searches to make sure that they were not stepping on a patent owner’s shoes when they launched a product.

Now that the threat of injunctions has been removed, the industry has taken a different tack: efficient infringement.

Efficient infringement

The notion of efficient infringement is where a company refuses to negotiate with an IP owner to get a patent licensing agreement.

Patent lawsuits are notoriously expensive, with a typical lawsuit costing on the order of $2-5M. Note that this is the cost for each side, meaning that the patent owner must be willing to lose upwards of $5M to defend their patent rights.

In other words, Big Tech has taken the position that it is cheaper to defend a lawsuit rather than negotiate up front with an IP owner. An upfront negotiation might mean that they take a license agreement from a patent owner and pay a $2M lump sum payment, but Big Tech would rather pay $5M on a lawsuit.

Because the threat of an injunction has been removed, the patent owner has virtually no negotiating power. The only way for a patent holder to get a meaningful license agreement is to have $5M at risk. This dramatically skews the power to the Big Company that infringes a patent.

However, there is a way for a patent holder to turn the tables: patent insurance[2].

With patent enforcement insurance, an inventor can have the resources to fight the Big Company.

The notion of efficient infringement is good business when patent owners do not have the resources to fight. But when the IP owners have insurance, they have all the resources in the world to fight the Big Company. At the end of the day, the IP owner just wants to license a patent for a fair amount.

What to do in the current situation?

The best solution is patent insurance.

The situation in intellectual property is nearly identical to healthcare. With the obnoxious costs of healthcare, nobody can afford to pay out of pocket.

The industry response to patent litigation means that only the very wealthy companies can afford litigation, but nobody else can.

Patent enforcement insurance turns that dynamic on its head.

The same way your health insurance gives you access to the best doctors and every procedure under the sun, patent enforcement insurance gives you access to the court system to resolve a patent dispute.

Note that patent lawsuits are usually just the opening salvo in a negotiation, although it used to be the last resort. Patent insurance makes sure that the infringer takes you seriously – that you have the means to defend yourself. Once they know you have that ability, you are negotiating as equals.