You – And Only You – Are Responsible for Your Patent

The sad story of how an inventor was taken advantage of by his patent attorney.

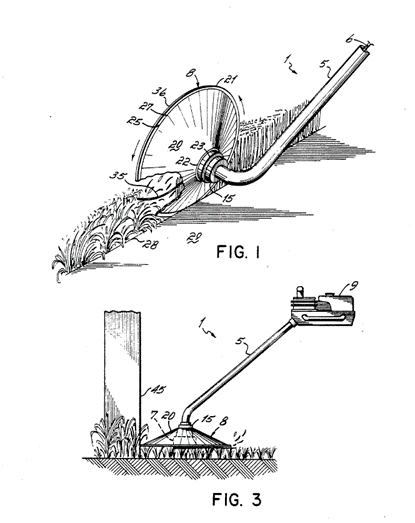

In 1989, Steven Byrne invented an accessory to a string trimmer – the ubiquitous ‘weed whacker’ used for landscaping. Mr. Byrne was a landscaper. He developed his invention so that he could use the string trimmer for edging a sidewalk. His accessory was a cone that help stabilize the string.[1]

Mr. Byrne was no different from any independent inventor. He had an idea that came from specific knowledge of his business. He saw a need and experimented with some solutions. When he was satisfied, he went to a patent attorney.

Mr. Byrne plopped down the money and the patent attorney delivered a patent a couple years later. Newly minted patent in hand, he and his attorney went to Black and Decker and attempted to get a license to his patent.

Black and Decker took one look at the patent, figured out that they could design around the claims, and promptly said “Thanks, but no thanks.” The next thing they knew, Black and Decker brought a similar product to market.

Mr. Byrne was upset, and justifiably so. He had just negotiated with Black and Decker for a license, but did not get it signed. The next thing he knew, Black and Decker was “infringing” his patent. Using the same patent attorney, he filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Black and Decker for stealing his idea.

Black and Decker was able to design around the claims because Byrne’s patent attorney made some changes that dramatically narrowed the claims. The patent attorney did this so that he could get over the hump with the patent examiner and move the case forward.

Once the patent issued, Mr. Byrne was elated. After all, the client wanted a patent and the patent attorney got a patent for him.

It is very common that, during the arguments with the examiner, a patent attorney will add limitations to make the examiner happy. Examiners need to feel comfortable that the proper scope of rights are being granted to the inventor, so they tend to err on the side of narrower claims rather than broader. The attorney knew he was limiting the claims narrower and narrower, but the client wanted a patent and the attorney delivered.

Mr. Byrne thought he was doing the right thing. Mr. Byrne was a landscaper and had no expertise in patents, so he hired a patent attorney. Mr. Byrne thought everything was taken care of, that the patent attorney would get a good patent. The patent attorney did what patent attorneys do – got a patent.

Mr. Byrne had not yet realized that it was his own patent attorney who caused the trouble with the license by getting an overly narrow patent, so he sued Black and Decker for patent infringement and stealing his idea.

Of course, he was paying his own patent attorney – the one who caused all the problems – to sue Black and Decker.

Mr. Byrne realized the cold, hard facts after he lost the patent infringement lawsuit: his patent was not as good as he thought. More than that, it was his patent attorney’s fault that Black and Decker was able to design around.

To dive into the weeds a bit, the invention was a cone that clamped to the end of a string trimmer. The trimmer’s string would slide against the wide end of the cone, keeping the string in a very straight plane. The patent attorney used the concept “planar surface” to describe the end of the cone where the string rubbed.

The term “planar surface” means that if you sat the wide end of the cone on a table top, there would be a flat surface that matched the table top.

Black and Decker were able to get around the patent by changing that “planar surface” to something else. It could have been a slight conical surface, a rounded surface, or something else. In any event, there was a simple, easy way to design-around the patent.

And the patent attorney never told his client about this weakness.

What is Mr. Byrne to do? He felt like his patent attorney let him down. After all, the patent attorney was the expert at patents and licensing. He was a landscaper with no experience with patents or the legal system at all.

Mr. Byrne sued his patent attorney for malpractice.

Mr. Byrne rightly believed his attorney let him down. The attorney was hired to get him a good patent – a licensable patent. As a client, he had no expertise to know if the attorney was doing a good job or not. He relied on the attorney’s expertise.

Turns out that Mr. Byrne lost the malpractice lawsuit, too.

The court said that the patent attorney’s duty of care was only to get a patent, not to get a good one. The attorney cannot be held responsible if the patent turns out to be worthless – that is the client’s responsibility. This may seem unfair, but it is how the system works.

The sad truth: it is the client’s fault – not the attorney’s – if the patents are worthless.

Entrepreneurs routinely put their faith in their patent attorneys to take care of everything. This faith is misplaced. It is the entrepreneur’s responsibility to manage their patent portfolio, for them to monitor what the attorneys are doing, and, sadly, are liable for anything the attorney produces.

Buyer beware.

[1] US Patent 5115870 “Flexible flail trimmer with combined guide and guard”, issued 26 May 1992, reissued as US RE34815 on 3 Jan 1995.