The Problems with Your Patent Attorney Owning Stock in Your Company

The Ethical Quandary

Patent attorneys are entrusted with the responsibility of safeguarding their clients’ intellectual property. This fiduciary duty requires them to act in the best interest of their clients, providing unbiased and objective legal advice. However, when a patent attorney owns stock in a client’s company, their financial interests conflict with their professional obligations.

Taking an ownership interest in a client, especially by owning stock in a private, early-stage company, creates more costs and more complexity – purely so the greedy attorney can hopefully get a windfall.

When a patent attorney owns stock, it does not ‘align interests’, it creates a conflict of interest.

Owning stock in a client a big problem – and there is no way around it.

A primary concern is the inherent conflict of interest. When a patent attorney has a financial stake in a client’s success, their judgment is compromised.

This may not be obvious at first, but consider a simple example. Let’s say a patent attorney has stock in a company, and there is an offer to buy the company from a strategic competitor. The patent attorney may be way behind on their boat payment, and may be desperate for cash. The possible sale would be great for the patent attorney, but may be awful for the company as a whole. How can the patent attorney offer any help to the CEO in this situation?

The answer is that the patent attorney must – without any exception – recuse themselves from any conversation about the sale of the company. The CEO must find another attorney who does not have the track record or history with the company, and probably cannot offer meaningful advice without an absurd amount of work.

Think about that: when the CEO of a startup company needs their attorney the most, the attorney must – without any exception – recuse themselves and offer no advice because they own a few shares of stock.

The American Bar Association (ABA) Model Rules of Professional Conduct are pretty clear: any conflict of interest is a big problem.

The Restatement (Third) of the Law Governing Lawyers further articulates that a lawyer may not represent a client if there is a substantial risk that the lawyer’s representation would be materially and adversely affected by the lawyer’s financial or other interests.

“Transparency and Disclosure”

First off, it is always a bad idea to push the boundaries of ethics, such as owning stock in a private company. Any attorney who is creating a conflict of interest where no conflict existed is not serving their client and is putting their personal financial gain far ahead of their client. This is unethical on its face, but many attorneys have far too much greed to pass it by, so the Bar Associations have twisted, complicated rules that try to justify behavior that their members insist on doing.

The Bar Associations say that if the investment/ownership stake is “substantial” and the patent attorney stands to make good money from it, the ownership is plainly unethical and improper. If the investment/ownership stake is not “substantial” and it might turn into a few extra dollars for the patent attorney, why risk your registration number, malpractice lawsuits, and the numerous conflicts of interest? (For clients, why do you want to do business with someone like this?) See the New Hampshire Bar Association’s analysis of stock ownership here.

Doing any investment/ownership stake is improper, but the greed of some attorneys is just too much temptation.

Threading the needle of an otherwise unethical transaction means disclosure and endless CYA letters. The attorney must “inform” the client of their contemplated unethical behavior and get buy off by the client.

The client must have the ability to hire *another* attorney to opine on whether the arrangement is “fair”. This is ludicrous, as must attorneys are taking stock because the company “can’t afford” their services, so the client almost always waives this requirement – to their detriment.

One of the ways the bar association twists themselves into knots in these conflict of interest situations is to suggest that the attorney who owns stock be supervised by an attorney who does not own stock. In other words, the client must now pay for an additional attorney to compensate for the unethical conflict of interest created by trying to ‘save money’ by issuing stock instead of paying the rack rate for services.

But really, is it worth it? The unmitigated greed of some attorneys for a nice windfall from a startup company by taking stock can jeopardize themselves and their clients. Just for a couple dollars?

Do these attorneys disclose that the company will now have to pay for two attorneys instead of one – just to make up for the fact that the first attorney created a conflict of interest that is adverse to their client?

Why do patent attorneys take stock ownership in their clients? The grass is always greener…

I completely understand why patent attorneys might want to take an ownership stake in a client. The client is usually an entrepreneur who can’t help themselves talking about how big their company is going to grow. It is addictive to be around the entrepreneur, and it the thought of a lottery ticket that pays off in the future can be overwhelming.

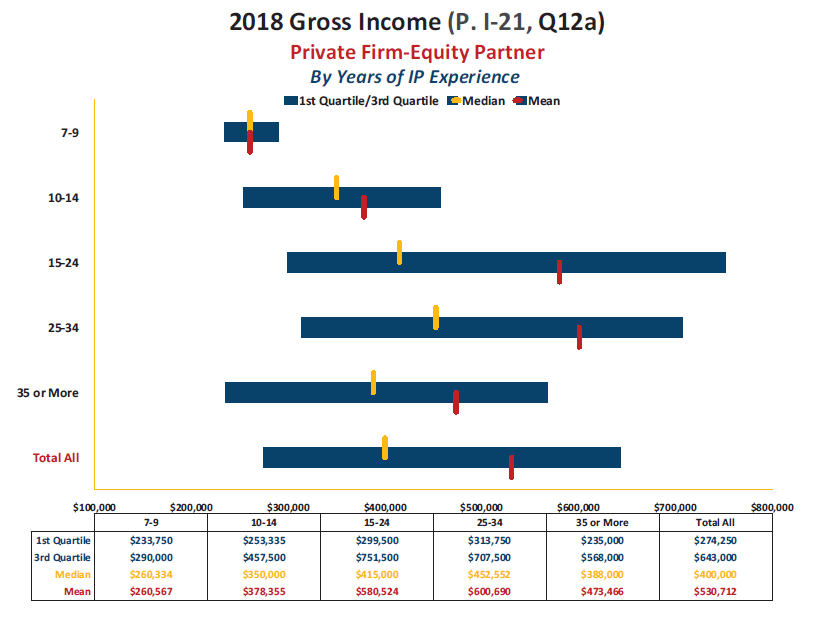

Compare that to the life of a patent attorney – someone who bills by the hour. They have no upside, no giant payoff in the future. Their life is to grind out patent after patent and slog through endless arguments with examiners. Yes, they can make a very, very comfortable living. See the data below from the 2019 AIPLA Economic Survey. Why do patent attorneys who are making an average salary over $500,000 need stock ownership in their client?

But the grass is always greener on the other side.

Anyone who bills by the hour or has a salary looks with envy at the entrepreneur who “risks it all” and has the thrill of a huge payoff. Similarly, the entrepreneur who puts it all on the line looks with envy at a patent attorney with a $500K annual income and think “I would be living the life of luxury if I were a patent attorney – without all the worry about putting food on the table.”

Attorneys who take stock ownership in their clients are wanting the thrill (and big payoff) of the entrepreneur but they are fundamentally unwilling to leave their $500K/year job. They want to have the reward without the risk. This is sleaze, pure and simple.

If the patent attorney had the guts to leave their cushy $500K/year job and start a company, I would respect that. But I have no respect for $500K/year attorneys who want a ‘bonus’ by taking stock in their clients and intentionally, deliberately, and knowingly creating a conflict of interest that will only cost their client in the long run.